The Goat and The Stars

About the Writer

Herbert Ernest Bates, CBE (16 May 1905 – 29 January 1974), better known as H. E. Bates, was an English writer and author. His best-known works include Love for Lydia, The Darling Buds of May, and My Uncle Silas. H. E. Bates was born on 16 May 1905 in Rushden, Northamptonshire, and educated at Kettering Grammar School. After leaving school, he worked as a reporter and a warehouse clerk.

Many of his stories depict life in the rural Midlands of England, particularly his native Northamptonshire. Bates was partial to taking long walks around the Northamptonshire countryside and this often provided the inspiration for his stories. Bates was a great lover of the countryside and this was exemplified in two volumes of essays entitled Through the Woods and Down the River. Both have been reprinted numerous times.

He discarded his first novel, written when he was in his late teens, but his second, and the first one to be published, The Two Sisters, was inspired by one of his midnight walks, which took him to the small village of Farndish. There, late at night, he saw a light burning in a cottage window and it was this that triggered the story.[1] At this time he was working briefly for the local newspaper in Wellingborough, a job which he hated, and then later at a local shoe-making warehouse, where he had time to write; in fact the whole of this first novel was written there. This was sent to, and rejected by, eight or nine publishers [2] until Jonathan Cape accepted it on the advice of its highly respected Reader, Edward Garnett. He was then twenty years old.

Source: Click Here

The Text

Every morning when he came into the town, going to school he would see this large and to him discomforting notice in blue and scarlet letters on a board outside the church. It had been there since a month before Christmas, ‘Annual Collection of Christmas Gifts in this Church on Christmas Eve. Help Us to Help Others. No Gift Too Large, None Too Small Give Generously.’ And then, in very much larger, staring and to him almost angry letters: ‘THIS MEANS YOU!’

He was a small, extremely puzzled-looking boy with a look of determination on his rather thin lips. Large brown trousers, which looked as if they had been cut down from his father’s, gave him a curious look of being out of place in the world. His hair looked as if it had been shorn off with sheep shears; his forehead had in it small, constant knots of perplexity. There was always mud on his boots and though he did not know it, there were times when he did not smell very sweet.

There were reasons for this smell. His father and mother had a small farm-holding of about ten acres, two miles out in the country. He was very fond of the goats, and it was his job to tether them on the roadside grass every morning and again, if he were home before darkness fell, to house them up in the disused pigsty for night. He treated the goats like friends. He knew that they were his friends. At frequent intervals the number of goats increased but his father could never sell the goats or even give them away. The boy was always glad about this and now they had thirteen goats; they had one, a kid of six weeks, all white, as pure as snow.

Every morning he went by the church the notice had some power of making him uneasy. It was the challenge in larger letter, THIS MEANS YOU that troubled him. More and more, as Christmas came near, he got into the habit of worrying about it. The notice seemed to spring out and hit him in the face; it seemed to make a hole in his conscience. It singled him out from the rest of the world: THIS MEANS YOU! Soon as he walked down in the country in the mornings and then again back in the evenings, he began to think if there was anything he could do about it. The notice, as time went on, made him feel as if it were watching him. Once he heard a story in which there had been a repetitive phrase which had also troubled him. ‘God Sees All.’ Gradually he got into his idea, that in addition to the notice, God too was watching him. In a way God and the notice were one.

It was not until the day before Christmas Eve that he decided to give the goat-kid to the church. He woke up with the decision, lying as it were, in his hands. It was as if it had been made for him and he knew there was no escaping it.

He had already grown deeply fond of the little goat, and it seemed to him a very great thing to sacrifice. That day there was no school and he spent most of the afternoon in the pigsty, kneeling on the strawed floor, combing the delicate milky hair of the little goat with a horse comb. In the sty the powerful congested smell of goats was solid but he did not notice it. It had long since penetrated his body and whatever clothes he wore.

By the time he had finished brushing and combing the goat he had begun to feel extremely proud and it. He had begun to get the idea that no other gift would be quite so beautiful. He did not know what other people would give. No gift was too great, none too small and things like toys and Christmas trees. There was no telling what would be given. He only knew that no one else would give quite what he was giving: something small and beautiful and living that was his friend.

When the goat-kid was ready he tied a piece of clean string round its neck and tethered it to a ring in the pigsty. His plan for taking it down into the town was simple. Every Christmas Eve he had to go and visit an aunt who kept a small corner grocery store in the town, and his aunt would give him a box of dates for his father, a box of chocolates for his mother and some sort of present for himself. All he had to do was to take the kid with him under cover of darkness. It was so light that he could carry it in his hands.

He got down into the town just before seven o’clock. Round the goat he had tied a clean meal sack, in case of rain. When the goat grew tired of walking he would carry it in his arms: then when he got tired of carrying it the goat would walk again. Only one thing troubled him. He did not know what the procedure at the church would be. There might, he imagined, be a long sort of desk, with men in charge. He would have to go to the desk and say, very simply, ‘I have brought this,’ and come away.

He was rather disconcerted to find the windows, of the church, full of light. He saw people, carrying parcels, going through the door. He saw the notice, a little torn by weather now, but still flaring at him: THIS MEANS YOU! And he felt slightly nervous as he stood on the other side of the street, with the kid at his side, like a little dog.

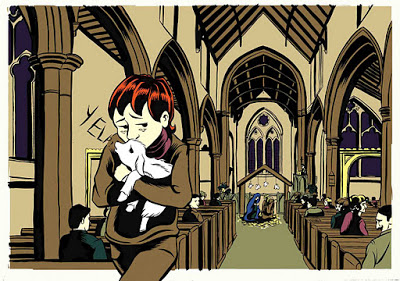

Finally when there were no more people going into to the church and it was very quiet, he decided to go in. There was already a sort of service in progress and he sat hastily down at the end of a pew, seeing in the other end of the church, in the soft light of candles, a reconstruction of the manger and the Child and the Wise Men who had followed the moving star. The stable and the manger reminded him of the pigsty where the goats were kept, and the first impression was that it would be a good sleeping-place for the kid.

He sat for some minutes before anything happened. A clergyman, speaking from the pulpit, was talking of the grace of giving. ‘They,’ he said, ‘brought frankincense and myrrh. You cannot bring frankincense, but what you have brought has a sweeter smell; the smell of sacrifice for others.’

As he spoke a man immediately in front of the boy turned to his wife, sniffing, and then whispering,

‘Funny smell of frankincense.’

‘Yes,’ she whispered. She too was sniffing mow. ‘I noticed it but didn’t like to say.’

They began to sniff together, like dogs. After some moments the woman turned and saw the boy, sitting tense and nervous, the knots of perplexity tight on his forehead and the goat in his arms.

‘Look round,’ she said,

The man turned and he too saw the goat.

‘Well,’ he said, ‘Well, no wonder!’

‘I hate them,’ the woman whispered. ‘I hate that smell.’

They began sniffing now with deliberation, attracting the attention of the other people, who too turned and saw the goat. In the pews about the boy there was a flutter of suppressed consternation. Finally, at the instigation of his wife, the man in front of the boy got up and went out.

He returned a minute later with an usher. Before going back to his pew he whispered: ‘There, my wife can’t stand the smell.’

A moment later the usher was whispering into the boy’s ear. ‘I’m afraid it’s hardly the right place for this. I’m afraid you’ll have to go out.’ At the approach of a strange person the little goat began to struggle, and let out a thin bleat of alarm.

As the boy got up it seemed to him that the whole church had turned and looked at him, partly in amusement, partly alarm, as though the presence of a kid were on the fringe of sacrilege.

Outside, the usher pointed down the steps ‘All right son, you run along.’

‘I wanted to give the goat,’ the boy said.

‘Yes I know,’ the man said, ‘but you got the wrong idea. A goat’s no use to anybody.’

The boy walked down the steps of the church into the street, the goat quiet now in his arms. He did not look at the notice which had said for so long THIS MEANS YOU because it was clear to him that he had made a sort of a mistake. It was clear that the notice did not mean him at all.

It was only by some other things that he was troubled. He had for long believed that at Christmas there must be snow on the ground, and a moving star.

But now there was no snow on the ground. There were no bells ringing and far above himself and the little goat the stars were still.

Source: click here